Read the edited transcript or listen to the full interview below

AK: Well, Alex, obviously we’ve been talking to you for years now about your disruptive technology fund, which has been going super, super well. Has the pandemic changed things either in reality or in the way you’re thinking about disruption?

AP: No, the pandemic didn’t change the way we think. COVID is what we call a ‘forcing function’- forcing changes that had already been in process. Examples of this include shortening supply chains, removing unnecessary steps out of transactions etc. In a sense, you can look at the supermarket itself as being an unnecessary part of the supply chain in the context of door-to-door delivery by Amazon or Woolworths. Contactless delivery is very much one of the things that comes out of a disruption – you don’t have to go up to the store to buy groceries.

Similarly, you don’t have to visit your doctor to have a health examination. I think there is a productivity bump that comes from this – not travelling around, trying to make appointments that could just as easily be covered off on via a teleconference link. And so almost all of our companies in one way or the other are beneficiaries of that. There’s a statistic from the US Bureau of Commerce statistic that shows from 2008 to 2020 eCommerce penetration went from around 8 to 17 per cent, and since March of this year, it’s gone from that level to 27 per cent in a matter of three or four months.

Are disruptive companies overpriced?

AK: What you’re talking about and what I think we’ve all seen really is a step-change in the use of technology as a result of the pandemic. But do you think that the stock market has more than priced that in, or has underpriced it? Where do you think the market stands in relation to that step-change?

AP: We wrote a big piece this week, Al, which you’ve probably already read about titled “FAANG Mania”.

AK: Yes.

AP: And, and the question is, is this FAANG thing a mania in the same way that we’ve had other manias in the past?

AK: I suppose I’m not talking about, yeah, everyone’s got an opinion about that. I’m really looking at your view about not so much whether it’s a mania, but I suppose it’s the same thing, isn’t it?

AP: Whether disruption is overpriced? Generally things get expensive and then they fall. The question is, is this time different? I think people are conflating high share prices with expensive companies. They’re two different things. The share price of Tesla is high and I do think it’s an expensive company, so we don’t own it anymore. The reason is because we believe the market is already factoring in 3 million vehicles sold for revenue of $180 billion in 2025. And if you do the numbers on that at say a 30 per cent gross margin, you wind up with $60 billion of operating profit, and you cut that in half for $30 billion of EBITDA at a 10 or 15 times multiple, that gives you the current market valuation. So that’s the Tesla pricing, but that’s too expensive in our view and so that’s not something that we hold. That’s a high share price, that’s expensive.

A high share price doesn’t mean a company is overvalued

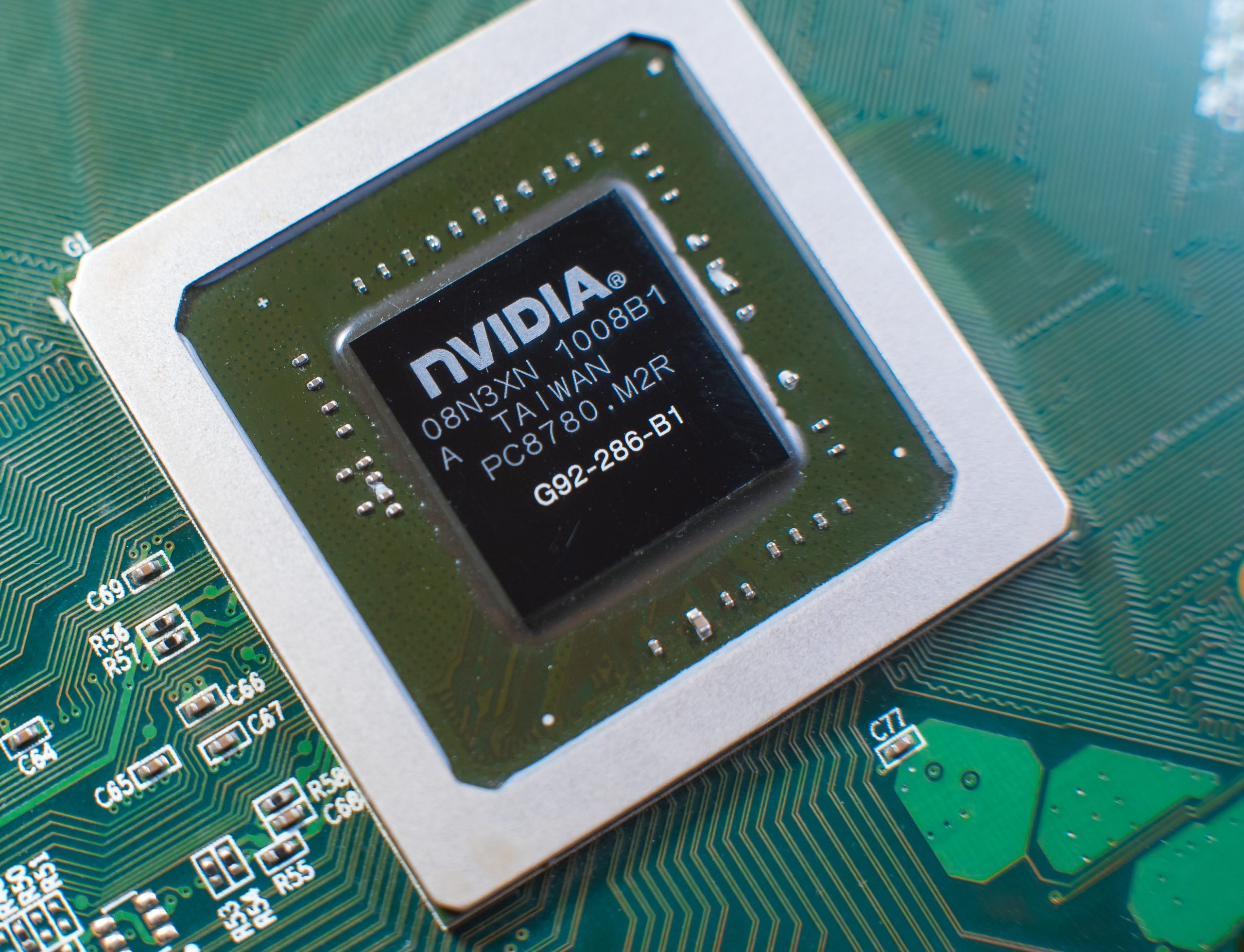

AP: There’s also a bunch of companies with high share prices, which we believe are not expensive or not as expensive. And the reasons that they’re not expensive is for example Apple or Amazon, or Alibaba, Nvidia or Xilinx, what’s happened is that these businesses have started off doing one kind of business, in the case of Apple selling phones, Amazon retailing, and over the last 10 years they’ve developed multiple other businesses. such as the Amazon Cloud Services that they bolt on, which in that case is more valuable than the company that they started with.

In the case of Apple, the services revenue is really what’s driving that. And the simple way to think about that is, you would know this Alan, I’m not aware of businesses that had 1.3 billion connected users, other than maybe Microsoft. I mean Comcast is a US cable operator that has 30 million subscribers, while Apple has 1.3 billion on one of its operating systems. It’s a relatively trivial exercise to roll out a payment platform called Apple Pay to a captive group of 1.3 billion people who are already using the operating system. They’ve added extra businesses into it. Amazon’s added Amazon Web Services. Alibaba has also added a cloud business, etc. Here are significant new businesses and people just know these companies for the things they did first, but they haven’t stood still.

AK: I think your distinction between an expensive share price and an expensive company is really interesting, and I wonder whether what you’re really talking about is the usefulness of the PE ratio. The expensiveness of the share price is really judged as to whether it’s the PEs, 18 times, which is what the market is, or is it 50 times. But you’re then saying, okay, well that’s one thing, but the business is another matter and that’s what you’re looking at and you’re valuing. Is that a fair way to look at it?

AP: It’s absolutely fair. I’ll just add a bit of colour to this, the trouble with PEs or EV/EBITDAs, is that they’re single period measures. The PE of the company in two years’ time doesn’t tell you what the PE of the company will be in three years’ time. As a valuation tool, it’s incredibly blunt. We do everything on a DCF basis and we really pay close attention, not to the next two years, because we think the market’s generally got that factored into it. We focus on two to five or even two to 10 years on the basis that the market has not paid sufficient attention to the future. We know the numbers that we put together will not be exact in terms of what happens between two years and 10 years, but we know that if we can find a good approximation for what they will be, and then run that back to a DCF, it produces a valuation, which is not a single period valuation.

It’s the valuation that comes out of looking at the company over a protracted number of years, seven or 10 or more, and discounting the cash flows back at a discount rate, which is appropriate, not just 5 per cent or 6 per cent, but sometimes as high as 25 per cent for a risky business.

AK: What discount rate are you using? Do you vary the discount rate?

AP: We have a series of five risk rank buckets with different discount rates. The discount rates, presently are 6%, 8%, 10%, 15% and 25% for the most risky companies. Apple would be a 6% and Amazon would be an 8%. A Tesla was 25% and then it went to risk rank 4, so it was a 15%.The underlying cost of capital assumption on a country basis comes from Aswath Damodaran, the Stern School NY university professor, sometimes referred to as the Dean of Valuation (Editor’s note – It’s not an official title, but it points to the importance of his skill in this area). We use his data as a base to inform us on valuation, but we add an overlay on top of it. We start on very sound principles, and we tweak it for what we need to do. Yes, so we don’t discount all companies back at the same rate because some companies have a lot more risk.

AK: It’s just the current US 10-year bond rate is 76 basis points 0.76, so, I mean, you could make an argument that your 6 per cent is too high.

AP: That’s absolutely true. And again, this is more or less out of an abundance of caution. Because there’s a risk premium on top of the risk-free rate, and then there’s the running it through the debt and equity mix, etc. We believe we have been conservative and the prices have gone up, so I guess that seems to be the case.

AK: Yeah, I suppose the only problem with using a high discount rate, I mean, I’m not saying you are, but if you were it would be to miss out on opportunities.

AP: Well, that’s precisely the point, right? You can’t hold Tesla at the same discount rate that you hold Apple. Tesla five years ago or even two years ago had massive execution risk. It had a massive business model risk. It had massive regulatory risk and Elon himself, was something of a risk to the company. And so those companies that we discount at very high rates, like Tesla, we can still buy, but we’re limited under our mandate to only owning 2% of them. So we control the risk through the discount rate and the position size, so to speak. We can take a 2% position in something that’s very risky. If the model works, or if the valuation stacks up using the higher discount rates, that’s how we have avoided the blow-ups, if you follow my drift.

AK: I do. You mentioned Xilinx before, that is actually your largest holding and it’s been a bit disappointing recently. Talk to us about Xilinx, what’s going on?

AP: Well, it’s under takeover right now. Look, it has disappointed a little bit, but it is a low risk company, and so risk adjusted the doubling of the share price worked for our investors. Another of our holdings, Nvidia, did better.

AK: I’m not saying it’s been that disappointing!

AP: No, it hasn’t been, it’s doubled. But of course, in the context of Nvidia, Nvidia has quadrupled. But Xilinx is an important part of everything that’s going on because it’s all about acceleration. And as you know Moore’s Law is breaking down because the geometry at the sub-atomic level may no longer sustain doubling of the numbers of transistors at process nodes below five nanometres.. And so the slack has been taken up in the companies like Xilinx and Nvidia, which provide the acceleration to enable Google for example to search for 67,000 requests per second.

It would never be possible to do that with a CPU alone. You could only do that with a CPU/GPU, which is what Google uses to process these queries. And there are literally thousands of real-world examples of that. You know, routing two Uber cars to pick up the closest passenger with a third stop involved is a very, very hard problem at scale, which can’t be done without access to accelerators, not just the CPU. That’s the way the game is all changing, we are big in that part of it because that’s the future of our investment performance. We’ve done very well out of it, but there’s more coming, of course.

AK: When you look at the cash flows, the future cash flows of these businesses, are you looking at 10 years? I mean, is that the sort of timeframe we’re talking about for these businesses?

AP: Yeah. We look at 10 years and even slightly more than 10-year cash flows and we’re careful about that. It would be a mistake to suffer from a lack of imagination from a company that’s grown its revenue from $1 billion to $100 billion, but then assume that it can’t grow its revenue from $100 billion to $1 trillion, over a period of years. But it would be a similar mistake, just picking any company that has gone from $1 billion to $100 billion of revenue, it would be a bit of a mistake to just assume that it grew at 5% for the next 10 years as well. So somewhere in between growing to the sky and 5% growth is where the number has to land. The sell side in our view, does not pay adequate attention for what happens after year two, that’s where all of our attention is.

AK: Right. In the five minutes remaining, Alex, are you thinking about new forms of disruption?

Yes.

What is new in disruptive companies?

AK: I mean, obviously you’ve been on Nvidia for quite a while now and Xilinx and sort of what’s going on in semiconductors, but are there new forms of disruptions that you are paying attention to?

AP: The most recent disruptive company that’s really surfaced in the last few years has been Roku. Roku, it’s a very interesting company and it’s been a fantastic performer for us, way better than Xilinx, actually. Free to air television, you know, channel seven, channel nine, that sort of thing in Australia, clears through the rooftop antenna, but in the US these free services mostly clear through a cable service. They’re not big on rooftop antennas in the US. But pretty much as people are turning off their cable service in favour of a Netflix or Disney or Apple TV+ there’s a whole lot of free channels that they lose that were previously on cable.

So what Roku does is it simply is a mechanism for surfacing content all around the world. There’s tens of thousands of channels on Roku, country and western music, cooking channel etc. And the genius of what Roku does and they’ve only been doing it for six years, it’s massively disrupted free television and cable television because they do what Facebook does in social media. They take a piece of content that’s maybe a country and western music on a Nashville channel and they note that you’re in Melbourne Alan, and they say, well, there’s no point advertising Walmart in Nashville to Alan, because he’s in Melbourne. Why don’t we just advertise Woolworths or Coles to him in Melbourne? And the publisher (ie music channel in Nashville) they get some of that revenue. Woolworths is happy because their products get advertised. And you’re happy because you get your country and western music channel for free with a little relevant advertising,

That’s an example, we say that it should never have existed, right? It should have been gobbled up by the majors, but there it stands. And it’s new, it’s a disruptor that’s only a few years old that is 100 per cent effective doing what it’s doing right now.

AK: Do they sell boxes?

AP: They started off selling sticks and boxes that go in the back of your television, but now 35% of the smart televisions that are sold in the US, come with a Roku operating system, and its largest single player, and growing super fast – 78% platform revenue growth in the latest quarter. What you’re actually buying is the operating system in your new television.

AK: Wow.

AP: Yeah and with everything that implies right. Once you’ve got an operating system and once that’s the default operating system and it is for 30% of televisions in the US then really that’s a platform, right, and so that’s just the way that rolls.

From a competitive perspective, Samsung is a great brand, but Samsung doesn’t really provide you with the interfaces to turn your television into an advertising funded app store. Right? So what Roku does is it turns your television into an app store the way Apple turns your phone into an app store and Google turns its Android into an app store. This is an app store for your TV, advertising funded, and Netflix is on it, right. So Roku and Netflix are not competitors and neither is Disney Plus or HBO Plus or any of the other things, right? Roku says, come one, come all. You’re all going to be on our operating system.

AK: Thanks a lot Alex, it’s great to talk, as usual.

AP: Thanks Al.

AK: That was Alex Pollak of Loftus Peak Asset Management.

Share this Post