By Alex Pollak, CIO Loftus Peak

By Alex Pollak, CIO Loftus Peak

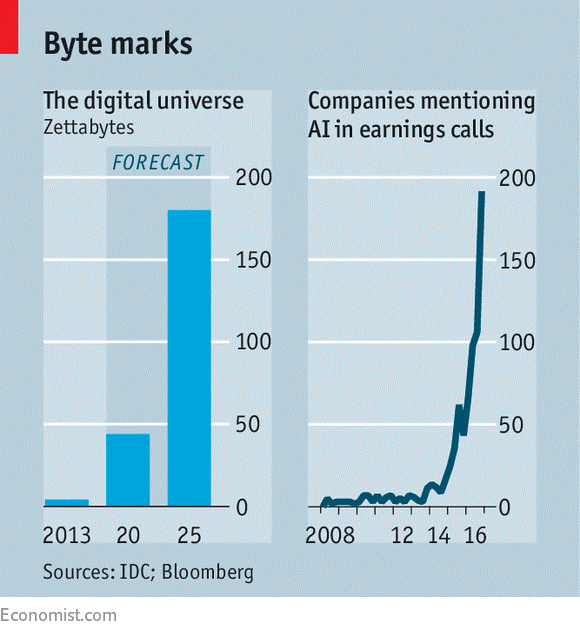

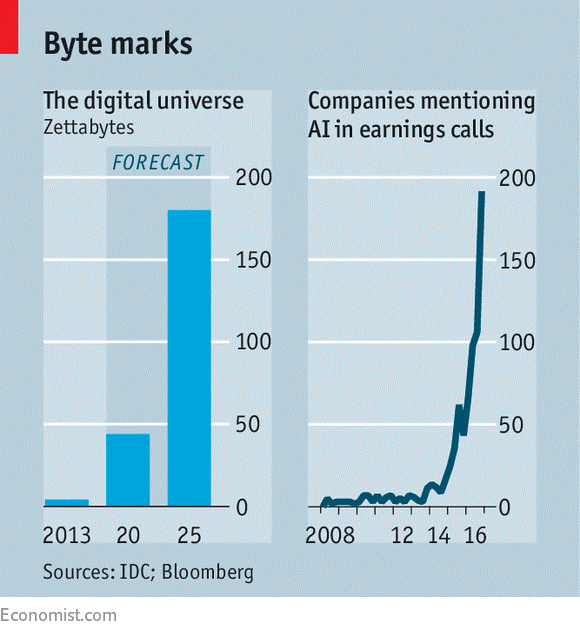

The Economist recently made reference to data as the new oil – the fuel on which the new economy runs. Here at Loftus Peak, we made some observations about knowledge networks, with commentary on how central they had become to business, and by way of proof, noted the change in make-up of the world’s top 10 companies. In 2007 four were oil companies, with some of the world’s biggest reserves of oil, today five are data companies – with some of the world’s biggest reserves of data.

Data on its own is useless without the ability to action it. Google talks about data as ingredients, with the value in the cooking, or applications which use it. Which is why the emergence of the data oligopolies and the houses they live in, the hyperscale data centres, are so important.

Want to work out the quickest way across town? Start a new business? Use a sprinkler to keep dogs from tearing up your lawn? Buy groceries, find out if you have genetically prone to an illness? Chances are you will have done so by accessing one of the hyperscale datacentres.

Just as fossil fuels were important to the world economy of the last century, new companies will find it hard to get to scale without relying on data and the datacentre.

For example, in Snapchat’s IPO filing, the company noted that its single largest cost was Google. It’s worth reproducing the actual comment: “We have committed to spend $2 billion with Google Cloud over the next five years and have built our software and computer systems to use computing, storage capabilities, bandwidth, and other services provided by Google, some of which do not have an alternative in the market. Any significant disruption of or interference with our use of Google Cloud would negatively impact our operations and our business would be seriously harmed.”

Snapchat has its own data – but not its own datacentre. And even the data it has are more useful when overlaid with the data that Google already produces (and stores in its datacentre). Unsurprisingly, Google founder Larry Page is on to this. When asked for access to the company’s data and computer power, he famously told the pioneering futurist Ray Kurzweil “I could try to give you some access to it. But it’s going to be very difficult to do that for an independent company.” Meaning any company that isn’t Google.

The reason this is so important going forward is because so much information which has been largely untapped on-line is visual; a photo can give important signals on age, sex, ethnicity, location, marital status etc. A streetscape can tell us not just the names of the businesses, but give clues as to size, viability, sustainability etc.

All of these visual data have been, well, visible – but not actionable, without the learning tools which have emerged literally in the past three years. Indeed, a major leap in machine learning capability, and so the usefulness of data, took place using the data sets available on Youtube – a Google computer identified a cat, without ever having been told, in programming language, what a cat is.

Machine learning makes possible differentiation based on all available data, not just computer code. These visual data will be part of another significant leap in the new economy in the next ten years, which should explain why Facebook and Apple are so keen to get the photo tagging working well.

In a very real sense, the only data that is relevant to the photographer may come as a result of the relationship with that person. But to a data miner, it may be everything else in the photo that isn’t the person – time, location, clothes and car, none of which were every really considered at the time.

The problems with the emerging data oligopoly, if that is what it is, are the same as the problems with all oligopolies. Amazon doesn’t just crowd out small retailers with its better tools, it may also result in smaller operators having to deal with Amazon in order to stay in business – meaning, for example network, cloud and logistics – to be found and shopped. And where Amazon enables, it charges. And those charges can be increased.

Certainly, there are entrepreneurs who are trying to create businesses by slicing the available data into more actionable forms. Some of these have become significant, such as Alteryx, founded in 2010, with over 1000 employees, or MapR, in which the Future Fund is invested, as well as a host of others.

But the world’s really big troves of data dwarf these operators, which in any case act more like ‘refiners’ than wells, to extend the oil analogy. Facebook committed (in statements to regulators) to keep separate the data in WhatsApp, which it bought for US$19b – but a few years later, appears to be backtracking. Alert users will already be aware that Facebook recently rejigged the WhatsApp privacy policy, which was a core attraction for users, with much less favourable terms of service essentially allowing the messaging service the right to commercialise user data as it pleased. Those who didn’t tick the box were kicked off the platform, naturally.

It is also possible that the really bad behaviour is not on show. Microsoft had a reputation for unconscionable conduct in dealing with competitors – maybe the big guys are doing the same in their dealings with potentially valuable upstarts, meaning that they may be using their balance sheets and market power to force them to sell out, on pain of competition, before they become significant.

Should these companies be broken up over time, like the US phone company AT&T or Standard Oil? They argue that their behaviour is not really harmful – consumers receive excellent mapping services for free, for example, with the true cost hidden, perhaps for years.

What is clear is that these data players are emerging as gatekeepers to the economy itself, with the ability to levy a charge on any business which is web-enabled. And today, that is every business.

Share this Post