Source: Shutterstock

If you have noticed that there are fewer new US programs on your Netflix feed, that’s because there has been both an actors’ and a writers’ strike in America. The same goes for Foxtel and Binge – the HBO content on which their businesses are built is also subject to the US talent strike.

But there are other big changes that are upending the entertainment industry model in the US, and as we know, almost every piece of content from the US in the end finds its way here, Allied to this, Netflix streaming has changed the way the small screen looks in Australia.

The Disney changes relate to the very core of the US industry, the cable businesses, on which virtually all television is carried (excluding the satellite players and some other legacy technologies).

For decades, the running assumption has been that traditional TV media players (Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, Paramount and Fox) could continue growing their businesses by increasing charges to their main US distribution channels, the cable companies, at a rate exceeding that which was lost due to cord-cutting (cable subscribers cancelling in favour of streamers like Netflix). In some parts of the US, it has been noted that in just three years the price of cable TV has ballooned from $100/month to $150/month – up 50%!

These companies had the power to do so because of ownership of tentpole sports content rights like the NFL, NBA and more. Live sport is the powerful glue holding the cable bundle together.

Disney does not have a friend in Charter

That was until last week when Charter communications, with 15 million TV subscribers through its cable service, said enough was enough. In response to Disney’s 10%+ increase for carriage of ESPN, Charter issued a press release titled “The Future of Multichannel Video: Moving Forward, Or Moving On.” It included the demand that if Charter were to accept the price rise, Disney would have to make available its ad-supported streaming services (Disney+ and ESPN+) to Charter’s eligible cable subscribers.

There was also the following slide, which was remarkable:

Source: Charter

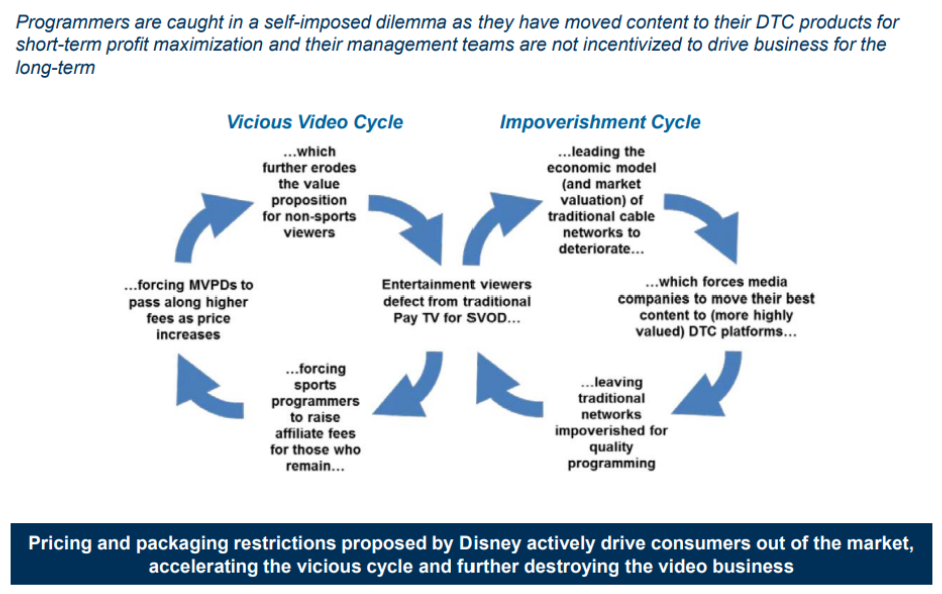

Charter was (rightfully) frustrated that Disney was hiking its prices for no additional value and that those price hikes were being used to fund its streaming service – both of which were accelerating the decline of its cable distribution business (in terms of subscribers and profitability). After all, why subscribe to cable for $150/month when you could get all of the general entertainment you ever wanted (and then some) by way of streaming services for $50/month?

Millions were “cutting the (cable) cord” each year as a result.

Accordingly, Charter was prepared to “largely exit the traditional video business” if Disney didn’t agree to its terms. The industry, and the cable business model in place since the 60s, had been put on notice. Read that sentence slowly: it means the end of the existing pay tv model.

At risk to Disney is US$2.2bn in annual affiliate fees and any associated advertising. At risk to Charter is the potential loss of subscribers as a result of the blackout right before the beginning of the NFL season. The effect of that would almost certainly be an exodus of Charter’s sport fans who would find what they were looking for elsewhere.

Source: Oscarrboltongreen

Disney blinked

As has happened in the past, the dispute was resolved at the eleventh hour. But in this case, for the first time possibly ever, it was the content owner, Disney, that wound up making the concessions – including acceding to Charter’s demands on its streaming services, albeit at a wholesale rate. In our view, Charter will not be the last of the US cable operators to demand such concessions.

This signifies a shift in power that will have implications for the way individuals consume entertainment, especially sports, and how much they pay for it, not just in the US, but globally.

Content is still king, but distribution is dominion

The cable bundle was not a bad business model.

In fact, it was arguably the best business model the content providers could have asked for: they were all participating in fantastic economics – at its peak the US TV market generated revenue of ~US$200bn per year – and by bundling all of the content together it effectively locked those users in and reduced churn (unsubscribes).

It is the lucrative nature of the bundling business model that explains why Charter made the move that it did. Charter is attempting to disrupt the cable bundle that is 70 years old with a streaming bundle.

Charter believes it still has an important part to play given it provides the cable over which 30m+ households in the US access the internet (the same one it offers for its cable/video services). It has a salesforce already trained in up-selling a video bundle and in-person store locations for customer service. And for what it’s worth, it seems to have strong-armed Disney into the beginnings of this process. Other internet service providers like Comcast, Frontier and Verizon are also likely to be lining up for this opportunity.

However, despite a role in the carriage of internet and streaming services which should be an obvious bundle, both US consumers and even those in Australia have not found this offer particularly compelling to date. It isn’t surprising these cable companies (in Australia Telstra and NBN) have often been described as providing a “dumb pipe”.

Which company will pull together the “new” bundle?

A smarter pipe for the rebundling of streaming services could be the television operating system itself. The operating system offers important advantages for the bundling of services, e.g. a smart, visually rich interface with the user, existing subscriptions (what don’t they have?) and viewing habits (what they watch the most/least). These are important in a world where surfacing good content becomes the basis of the monetisation of the new bundle.

Roku’s TV operating system, in nearly half of US households, has better distribution than any of the US internet companies. It already offers discounted subscriptions to many premium streaming services (Paramount+, Discovery+ and AMC+) on its platform. Amazon has a sizable US$1bn+ distribution business through its Prime Video Channels here, too.

Perhaps best positioned due to its global scale is Alphabet’s (Google’s) YouTube, which has over two billion users already in the habit of coming to its platform for user-generated video content. Is it too great a leap to imagine the platform offering a bundle of higher-end video content?

Too early to tell, but for cable bundle, sports content losing its stick

While the position of the streaming bundler remains up for grabs, what is clear is the direction of viewership in favour of streaming.

Just this week Warner Bros. Discovery signalled that it would make available its entire sports catalogue (which includes MLB, NHL, NBA and College Football games) by way of simulcast through an add-on to its streaming service Max. Another huge blow to the cable bundle, and a move we expect the other holders of sports rights will be forced to follow (Disney, Paramount and Comcast).

The more viewership that flows from traditional to streamed TV, the more dollars that are unlocked for the streaming ecosystem and the more revenue potential for the Fund’s beneficiaries of the streaming theme (namely Netflix and Roku).

Share this Post