Alex Pollak, CIO at Loftus Peak

We have had several smaller corrections in the five years since our inception, with the largest downturn in the December quarter of 2018. CNN noted at the time “The Dow fell 5.6%. The S&P 500 was down 6.2% and the Nasdaq fell 4%. December was a particularly dreadful month: The S&P 500 was down 9% and the Dow was down 8.7% — the worst December since 1931. In one seven-day stretch, the Dow fell by 350 points or more six times. This year’s Christmas Eve was the worst ever for the index.”

Since inception, we have generated solid returns based on a multi-year time frame. We believe the key to investor protection from broad market declines is delivered by our stock selection and portfolio construction process. Our process is inherently biased towards large market capitalisation quality companies which are expected to survive downturns due to strategic business positioning in secular growth trends and have strong balance sheets.

Portfolio construction

We run a large capitalisation concentrated portfolio and hence are much less exposed to the long tail of smaller companies. It may well be that individual returns from selected small capitalisation companies can do very well, but in our view a bias to the large capitalisation disruptors with solid cash flows and the ability to move into other adjacent businesses (eg Apple into music and TV) makes for a lower risk portfolio. Focusing on large capitalisation names has meant the portfolio’s median market capitalisation is currently US$81 billion, which has the added benefit of high liquidity and the ability to quickly move into cash where necessary.

Investment philosophy and valuation

Loftus Peak’s valuation methodology is based on the bedrock that the value of a share is the discounted value of its future cashflows. This approach was successfully refined over a decade at Loftus Peak’s predecessor firm TechInvest, where similarly consistent outperformance to that of Loftus Peak was achieved. (It is worth noting that key members of the Techinvest team continue to implement this investment approach under the Loftus Peak banner). The focus of our valuation model is on understanding the potential addressable market size of the companies in 2-5 years from now and the resulting margin profile.

These filters are part of the process to screen out companies which may be disruptors, but do not work as investments because of price.

Process in practice – Uber (UBER)

A simple case in point is Uber. There is little doubt that the company is up-ending the taxi industry, with a global disruption model which will ultimately replace the traditional transport model (taxis, hire cars etc). We avoided this company on listing, and thereafter, and continue to do so, for the simple reason that the numbers don’t really work.

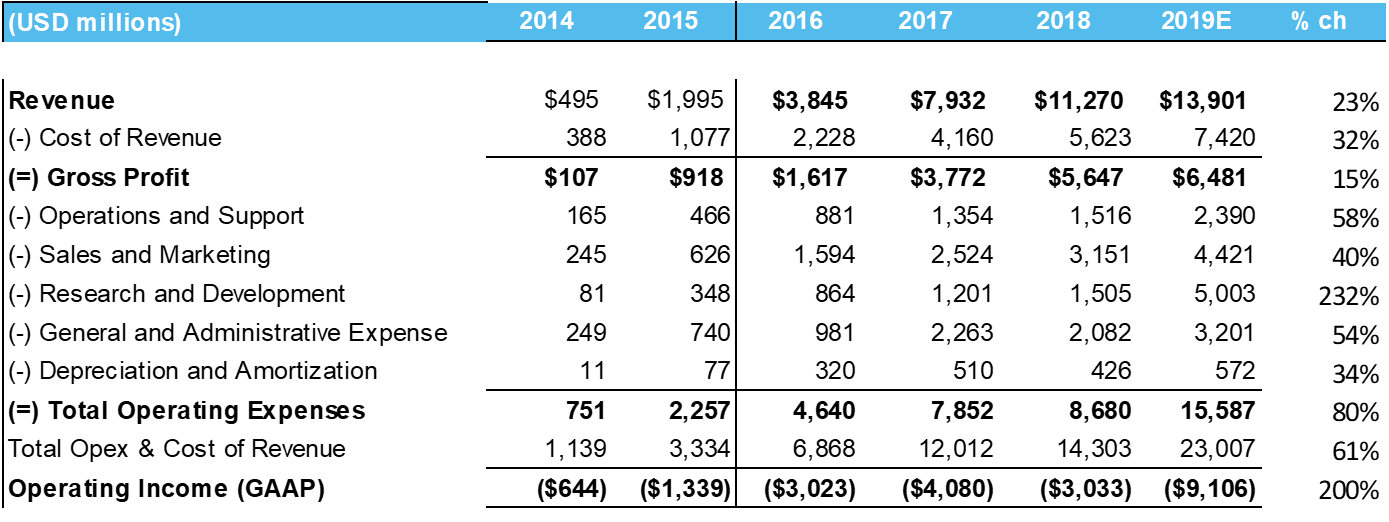

First, and most important, the losses from the group are not being reduced, but are widening, as the model (actuals to 2018, our estimates in 2019) below shows:

Uber: Not so much

Source: Company filings, 2019 Loftus Peak estimates

Forecast revenue in 2019 of US$13.9b (which itself is up 23%) is expected to yield only a 15% increase in gross profit; this is major red flag since the business reveals weak leverage (meaning that the amount of gross profit goes up by less than the increase in sales). This is exacerbated all the way down through the expense line items, such that the bottom line shows the operating loss (essentially pre-interest and tax earnings) tripling to -US$9b. Operating cashflows are similarly weak.

This would not automatically exclude the company from Loftus Peak portfolios. For example, if in coming years these losses lessened sufficiently – so that it achieved profitability fast enough – this would drive an increase in value in the company which would show in the multi-year discounted cash flows, and so share price.

Here it becomes a matter of judgement on the business itself. We know Lyft (and Grab, and Chinese player Didi, and Ola) are all competing with Uber – so there is likely to be increased competition. This implies that losses will not be narrowing enough any time soon, and indeed that revenue growth may even slow.

The way we believe the numbers will evolve means that the company does not easily fit into our portfolio – so it is disruptive, but the valuation doesn’t stack up.

Process in practice – Netflix (NFLX)

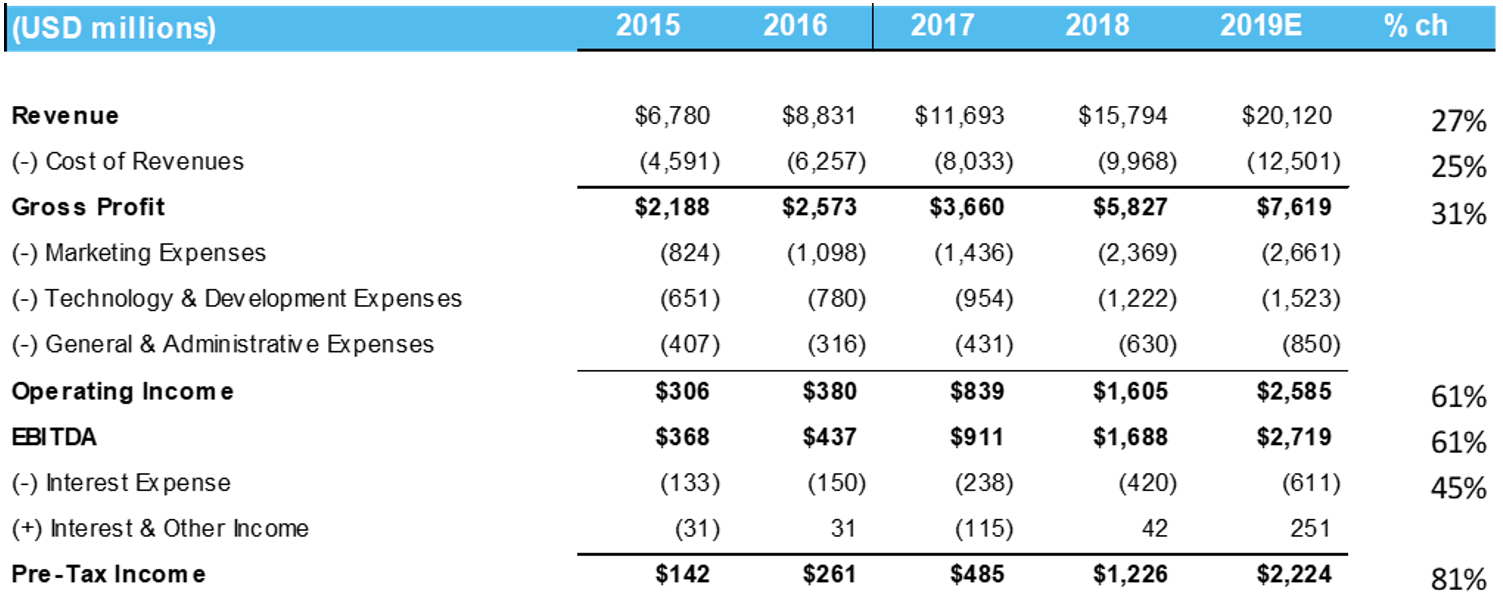

Netflix is a company that did make it into the portfolio, yet it often gets bad press for its results. We believe the company isn’t that well understood – it has been profitable for five years now, as the table below shows (again, all numbers are actuals except 2019)

Netflix: It works

Source: Company filings, 2019 Loftus Peak estimates

The questions which have been raised are around the company’s ongoing debt increases, which are necessary as it rolls out new content faster than its revenue grows. This amounts to an US$18b liability over the next four years (aside from that which it expenses annually against revenue) shown as a contingent liability. The company’s debt stands at around US$16b (after the additional US$2b it announced in October).

But as the table above shows, the company is on track to double its pre-tax income this year, having tripled it the year before. At this rate, the company is on track to generate more than US$30b in free cashflow within our forecast horizon. Revenue is still growing at around close to 30%.

We are not concerned about the competition from Disney+ and HBO/Warner, since the real prize is to capture time spent presently viewing linear television (whether cable or free to air, eg in Australia Foxtel or Seven/Nine/Ten). This market is yet to fall to streaming (though it is well in hand). To put numbers around this, there are more than 1.5b+ billion households around the world receiving cable or free to air TV signals, which over the next ten years could probably stream (as broadband capacity grows.) Netflix is in 150 million of those households; it’s a true growth business. Disney+ and HBO/Warner acknowledge this – they are walking away from their cable TV models towards their own Netflix-like streaming product, and sacrificing tens of billions of dollars of revenue in the process. Forget the theme parks, the real white-knuckle ride will be the one the shareholders of those two companies are on.

Other major contributors – Amazon (AMZN)

Meanwhile, the number one contributor to return in Loftus Peak portfolios over the past five years, Amazon, was chosen because it made the cut on both these screens. We bought the company in 2014 not for its retail business, but for its emerging place as the number one cloud provider in the world.

As we noted to clients in February 2015, when the Amazon price was around US$300/share: “The market bid up Amazon 20% on the decision to break out the numbers behind Amazon Web Services (AWS) its cloud-based web hosting business. AWS formed a major part of the 40% revenue increase in the “other revenue” line in the 10k filing, which was US$1.74b in the quarter. The market thought AWS was worth $28b (US$60/share). The 20% jump in the share price looks like the market digesting the news – AWS is already a very significant player with corporate clients like Netflix, Mashable etc.” We had done the work well before this and invested accordingly, because we had seen AWS business growth in the market and the impact this would have on valuation of the company.

How is Loftus Peak different to other managers?

Lastly, a note about the index managers. Irrespective of whether Uber makes it as an investment, if it finds inclusion in an index then the index players will likely hold it. It’s not that the managers themselves don’t understand how businesses work, just that the business model of index funds is to hold the index – whatever its composition. We take a much more nuanced approach.

Our multi-year DCF approach, which involves thorough internal debate on the assumptions around revenue, market size and profitability, coupled with our portfolio construction methodology is the edge that helps us protect the portfolios we manage from market downturns.

Share this Post