By Alex Pollak, CIO Loftus Peak

Key Takeaways:

- This correction is just that – the problems we are facing are objectively nowhere near as large as those of the GFC

- At that time, the situation globally was so bad that the then PM Kevin Rudd had to guarantee the Australian bank deposits

- We believe stocks should rebound over the coming months – and are positioning the Loftus Peak Global Disruption Fund to take advantage of this.

What happened in October, 2008?

The sell-off we have experienced globally is a result of rising interest rates as quantitative easing is unwound in the US and the sabre-rattling around tariffs, especially as regards China. The Australian dollar is collateral damage – at time of writing it is hovering just above US71c.

Is this the end? A week ago, on the tenth anniversary of the global financial crisis (October 2008, more or less) the AFR extracted a headline from the front page it published at that time. The headline (right) said “Rudd guarantees bank deposits”.

We don’t recommend that anyone base their financial expectations on a single data point, but it is useful to reflect on the seriousness of the problem then, to help understand where we are now. It was so bad that the government had to explicitly guarantee voters’ bank deposits.

They had of course seen the situation in the UK, where Northern Rock, a building society/bank, had daily queues of people outside it trying to take out money. At that time in Australia there were well-sourced reports of people making withdrawals only to put the cash into a safe deposit box in the same branch.

As an aside, I was at that point an operative of Macquarie Bank, and in regular director briefings it was noted that there were real questions about whether the Australian banks could raise finance internationally to fund their lending operations. The debt markets had effectively frozen. In providing the government guarantee, Rudd effectively underwrote the confidence in the banks’ solvency.

Back to today

The unwinding of US$4.3 trillion of quantitative easing is effectively reducing liquidity globally, which is bubbling up as doubts about sovereign bonds in Turkey, Argentina and Brazil, among others. Locally, there are other tells: house prices are falling in Australia as banks adjust the volume of lending (limiting interest-only, low-doc or investment property loans) rather than the price (ie not interest rates – so unusually clever for a bank).

Almost all bull runs take place against a backdrop of rising interest rates – central banks usually go into battle against an overheating economy and stock market, with inflation being the target. Raising rates is the blunt instrument of choice and equity markets ultimately get damaged. In a crash, badly damaged.

At the same time, whole industries are being disrupted – network television (streaming services like Netflix and Stan), retailing (it seems clear that Wesfarmers is spinning off Coles because it can’t find a buyer), manufacturing, transport (the switch from the petrol engine to battery) and telephony (there is a good chance Telstra will have its executive remuneration package rejected, quite correctly, since its management has failed to transition the company effectively in an NBN world).

Were companies overpriced?

There are undoubtedly pockets of overvaluation. Amazon at almost $2050 a share was stretched on North American retail (Amazon stock plus third party merchandise), as well as some dreaming built into the cloud business, and on one analysis we saw a double-count on the Prime membership (which is part of retail, and so should not be valued separately). It’s not that Amazon won’t get there – but it’s more fairly priced under US$1800/share.

Over the next two weeks we have a slew of earnings numbers including Netflix, Baidu, Google, Facebook and Amazon. The pull-back we have seen may reflect some wariness over whether these companies will continue to deliver – unfounded in the case of Netflix, which last night surged 11% in after-market trading as it delivered on revenue and subscribers and exceeded earnings handily (following a disappointing previous quarter on weaker subscriber growth).

Investors should have cottoned on to the regular periods of outperformance following earnings releases and adjusted their behaviour accordingly thus making the selldown seem somewhat counterintuitive.

Let’s not have any doubt. We are not going back to a world where runners carry a cd player on their hip, or tourists pack an instamatic camera in the carry-on, or indeed network television takes all the viewers.

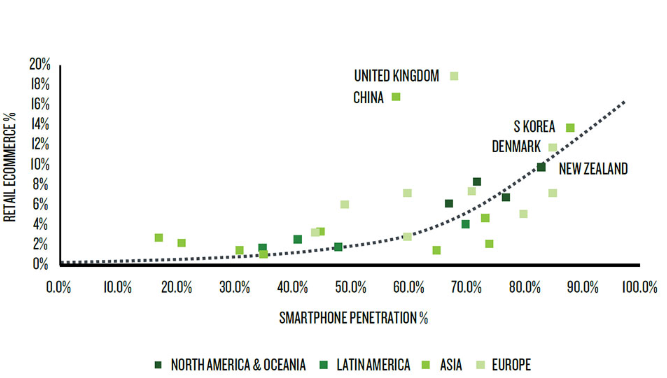

Sears, the iconic American retail, has just filed for bankruptcy protection. We published a chart last month which deserves a second run. It shows the correlation between the growth of e-commerce and smartphone penetration. As penetration went up through 80% for devices, e-commerce in North America, Asia and Europe also grew. But it is still only around 10% on these 2017 numbers, and could probably easily double as consumers globally become more comfortable with it. It is a rich irony, of course, that the chart is put out by Nielsen, which is in the business selling stuff through network TV in old-timey supermarkets.

Copyright © 2017 The Nielsen Company

Copyright © 2017 The Nielsen Company

So are we in line for a meltdown?

That’s not our view – we are a long way away from the crisis of the global banking system, or indeed the need for a new set of guarantees on bank deposits locally. Sure, we are later in the cycle than we were – but this could have been said any time in the past four years, during which time some markets (and our portfolio) has doubled.

Share this Post