By Alex Pollak, CIO Loftus Peak

From the Australian Financial Review

Now is the time to be extremely wary of value investments. The unprecedented change we are living through means that the risks of value investing have never been higher.

Here’s why: In a simplified world, there are two kinds of share investor: those who favour value and those who favour growth. The principles behind value investing (which have been the core of the approach of Warren Buffett and his many acolytes) mean value investors look for companies which are undervalued and so are trading at low multiples, or with asset backing in excess of their shareprices. There could be many reasons for this, like a cyclical downturn, or an accounting scandal. Sometimes even poor management can be part of the charm.

But in some cases the share price can be depressed due to structural issues. More on this shortly.

Growth investors, by contrast, look for businesses which have expanding addressable markets, and care less about whether valuations are high in a formal sense. They don’t care if a PE is more than 20x, as long as there is upside to push the value higher.

The chart below is instructive. It divides the ten year annualised performance of two MSCI global indices, growth and value, into one another. When the line is above zero, value is better, below zero it’s growth.

Source: Schroders

From 1984 until around 1997 value was outperforming growth by a critical few per cent each year. As the business case around the internet emerged, growth significantly outperformed value, with valuations of tech moving to stratospheric levels. There was a moment just a few years later – some marked it as the top – when AOL, a dial-up internet service provider with very skinny profits, was able to effect a zero-premium merger of equals with Time Warner.

Growth was already crashing – it took Time Warner 20 years to recover – and value stocks again outperformed, with the global financial crisis throwing up bargains which, for value investors, proved very profitable (although it is easy to forget investors still did poorly in many cases even as they thought they were buying deep value).

It was in this market that companies like Google and Facebook (which are important holdings in the Loftus Peak funds) grew, with big multiples which over time proved justified as profits grew well beyond expectations. Since the recovery from the GFC it has been a one-way ride for the real growth stocks.

There is nothing wrong or right about value or growth investing. We don’t really favour one over the other in generating returns – it’s a lot more nuanced than that. But today the whole argument is being broadly misunderstood and poorly applied as markets are being roiled by new businesses which run on models which are testing the boundaries of what makes a company valuable.

It’s not that cashflow isn’t important – it is – just as much as gearing, stockturn and interest coverage, all things we focus on daily. They remain as critical as they have always been. But the mechanisms for hitting success in these milestones are changing, which in turn is expanding the criteria for what makes a company valuable.

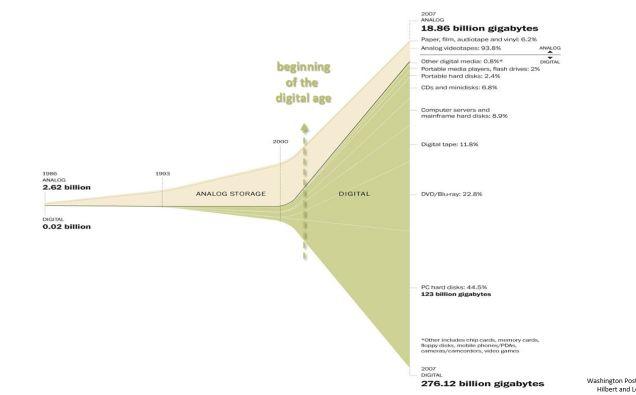

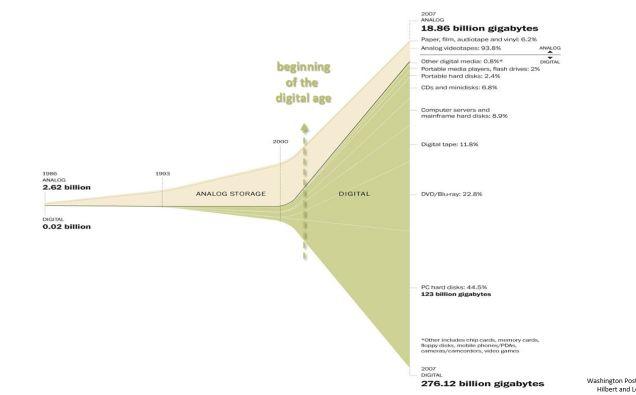

The reasons that markets are struggling so much with new valuation models is to do with the pace of change. Change has always been a factor, but it’s pace of change today that has never been greater. This is a fact which is objectively true. The sum of all recordable knowledge amounted to 2.64 billion gigabytes in 1900 (from a paper produced by University of Southern California) and it had doubled every hundred years before that. It doubled 9 times in the thirty years to 2007, with each subsequent doubling taking less time.

Hilbert, M., & López, P. (2011). The World’s Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information. Science, 332(6025), 60 –65.

So the pace of change continues to accelerate, and with it the boundaries of what is considered prudent investing.

The problems around this pace of change is that it can result in the de-rating of a lot blue-chip companies (as growth companies take over) making them look like value plays, when in fact they are structurally challenged and deeply flawed.

The value plays of today – at least many of them – are not just underloved stocks that will ulmimately rebound. They are in long term structural decline.

Thus it is that in 1910 investors may have thought it was a masterstroke to load up on businesses making carriages for horse-drawn transport. Even for those that thought the car was a better idea, the problem was the network of gas stations required to fuel them. It was never going to catch on, they thought.

The same could be said about investors in Kodak in the 90’s, who probably viewed the opportunity to buy stock in the company at ‘value’ as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. They thought it wasn’t different – that Kodak was just a deep value play which would recover. But it wasn’t.

It won’t always be like this. There will come a time soon enough when for whatever reason the pendulum will swing back – but many ‘carriage’ companies won’t be part of that swing.

Buffett himself, and his partner Charlie Munger, have re-canted to some degree on the value rhetoric in recent years. Buffett was long a technology bear, saying that it was impossible to make money there because the lifecycles of tech companies were too short (so there was no long term value). Berkshire Hathaway is one of the largest single shareholders in Apple today with a US$20b position.

For the global car companies like GM, Ford and VW, which are trading on sub-ten PER’s, electrification, ride-sharing and autonomous driving may be the reasons these companies are ‘cheap’.

A large value based Australian fund manager, a former client of mine, once took a very large (almost 10% of the company, or about $100m) position in PMP Communications, a Murdoch spin-off in Australia, which wound up trading on a single digit PE. Asked about the future of the position, the fund manager just shook his head and muttered “we are stuck”. It took years to get out.

Not value. Cheap for a reason.

Want to know how to invest with Loftus Peak? Click here to access our ASX listed mFund LOF01

Share this Post

March 2026 Update+

06 Mar 2026Artificial Intelligence roils sharemarkets

26 Feb 2026February 2026 Update+

16 Feb 2026Here come the Chinese robots!

28 Jan 2026